I was sitting at the dining room table with my father when I said it.

We were playing backgammon while T and our relatives were sitting behind me in the living room, watching television. I could see the steam rising from the cup of tea he had just poured himself. My tongue was still tingling from the single-malt Scotch sitting in front of me. I smiled as I took my turn; I was about to beat my father handily for the second straight game. Then, while my father was getting ready to roll the dice, I blurted it out.

“Tell me some Grandpa stories.”

My father stopped shaking the dice and looked at me. The edges of his lips curved upwards in the slightest hint of a smile.

“I can tell you stories or I can focus on the game. I can’t do both.”

I chuckled and said we should finish playing first. In retrospect, I should have quit while I was ahead and had him tell the stories; he ended up winning the best-of-five series.1 When we had finished, he leaned back in his chair, clasped his fingers in front of him and asked, “What kinds of stories are you looking for?”

I thought for a minute before answering.

“I don’t really know who Grandpa was.”

I knew a lot about my mother’s parents. I knew about their childhoods living in India, their immigration to the United States and their lives as parents and grandparents. I knew a fair amount about my father’s mother, from being born in Mexico and raised there and in Cuba to living in the United States after she got married. I knew that she and my father moved with my grandfather every two years with each new military station assignment. I knew these stories because my grandparents were all still alive and had been able to tell me themselves.

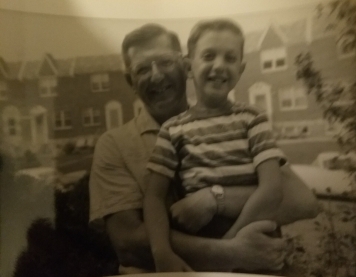

But it occurred to me recently that I knew very little about my father’s father, who passed away when I was very young. I knew he had been a radio and  communications operator in the Air Force and that he served in North Africa during World War II. I knew one or two stories about him joining the military and about his interactions with his relatives. I knew that anytime I saw Harry Caray on television when I was little, I pointed to the screen and said, “Grandpa!” because they both had white hair and glasses. (This picture of him and my grandmother was obviously taken long before his hair turned white.) And I knew that I had been named for him.2 But that was about it.

communications operator in the Air Force and that he served in North Africa during World War II. I knew one or two stories about him joining the military and about his interactions with his relatives. I knew that anytime I saw Harry Caray on television when I was little, I pointed to the screen and said, “Grandpa!” because they both had white hair and glasses. (This picture of him and my grandmother was obviously taken long before his hair turned white.) And I knew that I had been named for him.2 But that was about it.

I decided that I wanted to know everything. What kind of a husband had he been? Had he been an involved father? How did he get along with other people? What did he do for fun?

“Maybe just start at the beginning?” I suggested.

My father shrugged and pursed his lips. His eyebrows raised slightly as his face took on the expression that I know I make all too often. It’s the face I make whenever I’m about to start a task and I’m not sure how things are going to turn out. It’s the expression that says, “Okay, here goes nothing.”

He began speaking about my grandfather’s life as a young man, from making a living as an ice delivery man to driving his brother from Philadelphia to Tucson. He told me how my grandfather joined the Air Force, made it through basic training and had begun his introductory flight lessons before someone realized he was wearing glasses. That’s why he ended up as a radio operator; military pilots can’t wear corrective lenses. He spoke about his relationship with my grandfather, his memories of the interactions between his parents and the ways my grandfather’s personality changed as he got older.

I was surprised by the conversation. The bits and pieces I had heard about my grandfather previously had been largely positive. My grandfather was, by most accounts,  fairly well-liked and treated people well. He made decisions rationally and served his country both in times of war and peace. And yet, there were aspects of his personality that were decidedly less so, like his rigidity in terms of his expectations of others or his limitations as a father and husband. I suppose I should not have been shocked to hear that my grandfather had imperfections; he was human, after all. I wouldn’t say I was disappointed but I certainly found myself with some new perspectives about my father and his parents.

fairly well-liked and treated people well. He made decisions rationally and served his country both in times of war and peace. And yet, there were aspects of his personality that were decidedly less so, like his rigidity in terms of his expectations of others or his limitations as a father and husband. I suppose I should not have been shocked to hear that my grandfather had imperfections; he was human, after all. I wouldn’t say I was disappointed but I certainly found myself with some new perspectives about my father and his parents.

That being said, I also don’t regret asking about my grandfather. I asked the questions because I was looking for a stronger connection to my past and I found what I was looking for. Part of growing up is coming to the realization that our parents aren’t invincible beings who have all the answers.3 We all have to come to grips with the knowledge that our parents and grandparents have strengths and weaknesses and that some of their decisions turned out better than others. Our kids will go through the same process with us as they get older. We just have to try to have compassion for those who came before us so that we can understand where they came from. Hopefully, our children will try to find the same compassion when they think about us.

1. He killed me in those games. The second game was a double game; he got all of his pieces off the board before I got any, which means that his victory counted for two games. The tiebreaker was a single game but it really wasn’t close.↩

2. My grandfather’s name was Hyman, but my father said he never would have forced that on me. Instead, he and my mother named me Aaron, which, in Hebrew, is Aharon. The Hebrew word, har, means “mountain.” Hyman became “high man,” which became “mountain dweller,” which became Aaron.↩

3. With all due respect to Dennis Green, they might not be who we thought they were.↩